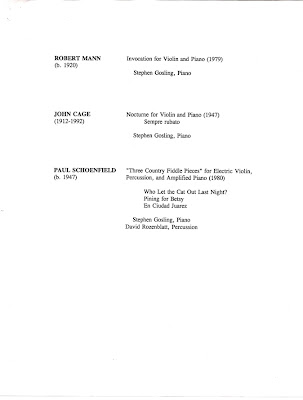

In 1993, my third and final year studying violin at Juilliard, I presented An Evening of American Music in Paul Recital Hall, with music by six American composers from the second half of the 20th century. Everyone on the program was still alive at the time (and still is, come to think of it), except John Cage, who had died that year. That meant I was able to play for and / or interview five of the six composers: John Corigliano (the Sonata for violin and piano), Elliott Carter (the Duo for violin and piano), Philip Glass (Knee Play 4, for violin and men's chorus, from Einstein on the Beach), my violin teacher Robert Mann (Invocation for violin and piano), and Paul Schonfield (Three Country Fiddle Pieces for electric violin, piano, and percussion). For the Cage Nocturne (violin and piano) I played for and interviewed Anahid Ajemian, who had premiered the work.

Apparently, being included on the American recital was a good omen for longevity. Bobby Mann is still teaching and composing at 90, and Carter, 102, is at the height of his powers.

Philip Glass - one of the junior members of that group - turns 74 today, and Archive Fever is celebrating the occasion by pulling the Knee Play 4 from the video vault and publishing, for the first time since the program notes were Xeroxed for the American recital, the interview I did with him November 22nd, 1993. He was incredibly lovely and generous to me and my fellow musicians, inviting us to his home downtown and even crafting an alternate ending for the piece, which is written to segue into the next act of the opera. An unexplored corner of the archive might have those extra measures in his handwriting.

I encountered Einstein on the Beach as a twelve-year-old, when the premiere recording was hot off the press, and inside that glossy black boxed set of records a mind-altering aesthetic adventure awaited me. All those electric organs and urban flute menageries and the sound of Iris Hiskey singing "Bed" with no vibrato - it broke open not just the vocabulary of music but its capacity to give me pleasure. Einstein remains one of my favorite operas, and that first encounter stands as one of the most viscerally, psychedelically powerful experiences of my life.

Happy birthday Philip Glass!

Knee Play 4 from the opera Einstein on the Beach, by Philip Glass

Interview with Philip Glass

November 22nd, 1993

Paul Festa: First of all, what is a knee play, and where did it get its name?

Philip Glass: A knee play - it's a part of the body that connects different parts; it's a small part which connects two larger parts. In the context of a dramatic work, it's a connecting piece, so it's not really an interlude, which would be kind of an absence of something, this is really about connection. Bob [Wilson] invented the idea of a knee play as a connecting place of the piece. So there are five knee plays, one at the beginning, one at the end and three throughout.

PF: What attracted you to Einstein as an operatic character, and what is the significance of his having an instrumental, rather than a vocal role, in the opera?

PG: We were looking for a portrait of a well-known person; the idea of this opera was that it would be about someone that everyone knew. And if everybody knew about him, then we didn't have to tell the story in any direct way; we leave the problem of a narrative story because everyone knew the story to begin with. We talked about a number of people. Einstein was the one we chose because he was the one we both felt we responded to.

PF: Who else was on your short list?

PG: Oh, Gandhi was, and I made an opera about Gandhi after that...the Satyagraha. Bob was interested in Stalin and Hitler, but I wasn't. (laughs) He'd made an opera called The Life and Times of Josef Stalin, in which Josef Stalin never appears. But I was interested in more positive kinds of people, in a way. The idea was to find that the character becomes a focus, it becomes an occasion to make it a theater piece - if you choose something which is very well-known, then it gives you a lot of freedom to become more abstract. It's important, when possible, to connect a character - if there could be a built-in musical connection it's preferable. For example, if one would do an opera about, let's say, Caruso, it would be great because it would be an opera about someone who could sing. It's a little strange to do operas about people who never could sing. An opera about Gandhi, where Gandhi is singing, and there is no record of him having been able to sing at all...

PF: What about Columbus?

PG: Same thing. So that when a character has a musical connection, like in the case of Einstein - he actually played the violin - it's a real opportunity that you don't pass up. It's a way of connecting the character to the actual music itself. And it's done structurally, because since Einstein was a violinist, he would play the violin in the piece. It would be a real life connection to an abstract musical idea.

PF: The overall effect of the knee play is quite beautiful, but Einstein is working pretty hard at his arpeggios. Is he practicing?

PG: No. No he isn't. Some people might think so. It will be interesting for you to see the piece tonight [the November 22nd performance of the opera at the Brooklyn Academy of Music] because there's no doubt, when you see Greg Fulkerson play, that the piece is about passion, not about - though there is always discipline in music, as we know - and any musician knows that. But the way Greg plays the piece - and the way you play too, for that matter - it has to do with musical values that have very little to do with playing scales. It's a sad misconception of music that it's about practicing. It comes up - it's not a bad question, because it does come up now and then. People say, oh, it's just like practicing scales. Well, of course, they absolutely have no idea about how to play a scale. If you really knew how to play a scale beautifully, that's almost all you would need. The ending of Satyagraha is a good example of that.

PF: You've objected to the use of the term "minimalism" to describe your music. Is there anything meaningful about the term, and is there another which more accurately categorizes your music?

PG: Yes; it was meaningful between the years 1965 and 1974, when there was a conscious musical movement that opposed itself to what was then the contemporary musical movement of the time: the music of Carter and Boulez and the serial school, which were the people who, when I was a young man, when I was your age, that was the music we studied. That's how long ago that was. But my generation of composers really wanted to set up a different kind of music, and I spent ten years developing a very reductive style. But when I began to work in the theater, it really was the end of that. The main reason is that with creative minimalism, less is more, but theater is not like that at all - it's more is more. Theater is not a reductive form; it's an inclusive form. So that's one thing. It's actually very simple, what I do, but it's hard for people to figure it out. I'm a theater composer. That's actually the long and the short of it. That's basically what I do. Everything I do - almost everything - is for the theater, with a few exceptions. So what I do is theater music. It's such an obvious thing that no one thinks of it. When you think about it, I've done eleven operas, five ballets, and, you know, dozens of scores for theater.

PF: How do you see your role in the tradition of Western classical music? Have you built something continuous out of the tradition?

Oh, absolutely. Definitely. You only have to look at my background to see that. Not only did I finish Juilliard with a Master's degree - I began music when I was eight - but I studied with Nadia Boulanger. I had the most classical musical education of my generation, practically. I don't know anyone who did as much as I did in terms of musical education in making a conscious tie with the classical tradition. What's confusing for people is that at a certain point, I began including non-Western music, when I began working with Ravi Shankar. Starting in 1965, I started to expand into non-Western music and that kind of threw people off. But I don't think there's any doubt, if you look at Einstein, just in terms of voice leading or in terms of traditional rules of counterpoint and harmony you can see what's going on. It's obvious what it is. It's obvious to musicians. If you look at the music, it's very much in the tradition of harmony and counterpoint, the voice leading practice of the 18th century. I don't know what else to say about it. (laughs)

PF: I guess my question is whether the route that you took broke off more suddenly than...

PG: It did appear to. But Paul, you only have to think into the past. Schoenberg appeared to have done the same thing. Wagner appeared to do that. The big changes in music happen at great intervals of 40 or 50 years, and they're usually such a shock that it takes people 40 or 50 years to catch up with it. I don't think it's as big a shock as other people do. I think in time it will not be seen as such a big break. It just appears to be that way now because of the proximity of the events.

PF: In the New York Times, Edward Rothstein wrote, "It is a tribute to [Glass'] gifts that he has managed to make the borders between high and low so porous, while demonstrating that the distinction has meaning." What do you think about that?

PG: Well, I don't think much of critics, generally. It's a complimentary remark, certainly, but those are not my intentions at all. I'm not breaking down the borders between pop music and classical music. People think that's what it is, but I've never thought about it that way. I simply don't think about that. It's a critic's game; it's not a strategy of mine.

PF: Last question. In what way is your music distinctly American?

PG: Well that's a very good question - it's a hard question to answer. I know it is because when I take it to Europe, that's what it - I remember going to Europe eight or ten years, fifteen years ago, and I noticed they weren't doing a lot of other music by other American composers. I didn't hear a lot of Carter or Wuorinen or Druckman - I didn't hear that in Europe. And I said, "How come you're not playing this music over here?" And they said, "Oh, we have that over here, but we don't have you." (laughs) I thought that was an interesting comment, "Oh we have lots of that over here." When I'm in Europe the music sounds distinctly American. Even not only American, but it sounds like it comes from New York - and if you live in New York, you know what part of New York. You could even locate the part of town. At the same time, it's interesting that it travels so well. We're doing it (Einstein on the Beach) this year in Australia, Brazil, Japan, Europe - and the music is recognized instantly as music and yet it has a - I don't know if it has the same things that you hear in Copland and Gershwin, the penchant Americans have for a particular kind of rhythm. I think it comes out of the American language, out of the way we speak. The cadence of our language is different from the English that's spoken in England. I think it comes out of that - I think it comes out of the way we walk, the way we move. There is a distinctive physicality about American life which comes in movement and speech and I think it also comes out of music and we hear it in Cole Porter or Duke Ellington or Elliott Carter - yeah, we do hear it in Elliott Carter. The first quartet is a very jazzy piece. I think Americans are the best people equipped to play that kind of music. So in that way I think the Europeans were wrong, in terms of him, at any rate.